Something went wrong trying to save https://www.npr.org/transcripts/3912464.

"And that our legacies might not look like traditional inheritances."

"But freedom and unfreedom are sometimes knotted together tightly."

"But you can’t dissociate in the sea. Not without risking your life."

"To be near the sea is to be humbled by its magnitude, to watch your priorities be reordered to its scale. What are self-consciousness, fear of the future, existential worries, to the ocean?"

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/22/magazine/playa-zipolite-nude-beach-mexico.html

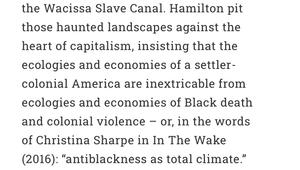

"how slavery's violences emerge within the contemporary conditions of spatial, legal, psychic, material, and other dimensions of Black non/being as well as in Black modes of resistance" (14) —Christina Sharpe

"In the wake, the past that is not past reappears, always, to rupture the present." (9) —Christina Sharpe

“Situating ourselves at the cellular levels shows us that our supposedly discrete bodies are actually complex ecosystems of cells, bacteria, and other organisms, which challenges our notion of individuality and sovereignty”—Jayna Brown

"From a scientific standpoint, there is a molecular interconnectedness between humans and the sea; read through an African American historical prism, humans, who lost their lives in the currents, have, by their very materiality, changed the composition of the waters. Altering the bones that have lain on the ocean floor for centuries, the Atlantic is part of the ancestral past and thus inherent in the collective memory." —Anissa Janine Wardi

As the American South’s slavocracy fell apart in the aftermath of the Civil War, coastal regions that were once valued for their role in facilitating the existence of slavery saw their worth diminish. The devaluation of the South’s coastal areas actually started prior to the Civil War, as “unsustainable farming” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 7), “unmanageable labor regimes” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 7), “inherent environmental limitations and vulnerabilities” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 7), and even the presence of “mosquitoes, predatory animals, dense forests, and sandy, nonarable soil” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 7) made coastal places unappealing. With the emergence of worthless coastal properties, opportunities for land ownership were available for a population of newly freed Blacks. Soon, coastal sites acquired and owned by Blacks dotted the South.

Because many Black people shifted from being propertyless laborers to landowners, acquired coastal regions became places that were representative of liberation, especially...

In the late 1890s, a group of administrators from the Hampton Institute (now known as Hampton University) navigated the real estate market in search of a waterfront property that would be appropriate for the construction of a building that would house student athletics and also out-of-town guests visiting the Institute (Kahrl, 2012; St. John Erickson, 2015; Stephens, n.d.). The administrators’ search for the perfect location ended after they bought one and a half acres of land from a “viciously racist beachfront property owner” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 181) who kept a “large sign on the beach that read ‘Niggers, dogs, and Chinamen not allowed on this beach’” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 181). Hampton historians allege that the unlikely transaction between the two parties took place because the original property owner had a dispute with his neighbors, prompting him to sell his beachfront plot to the “most undesirable buyers imaginable” (Kahrl, 2012, p. 181).

“Most groups preserve their [collective] memories by spatializing them: they ‘engrave their form in some way upon the soil and retrieve their collective remembrances within the spatial framework thus defined’” —Kathleen Brogan

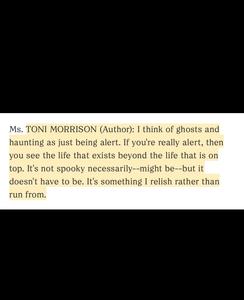

“haunted places are the only ones people can live in” —Michel de Certeau

“Every place has its own story, or even a proliferation of stories, and every spatial practice constitutes a form of re-narrating and re-writing a place”—Michel de Certeau

“places are processes” —Kathleen Brogan

As discussed by Anissa Janine Wardi (2011) in the book, Water and African American Memory: An Ecocritical Perspective, memories of Black pain in outdoors spaces often construct the natural realm as a “politically charged racialized topography, imprinted with a history of slavery, racism, and barbaric Jim Crow practices, where the woods are not merely unspoiled sites of wilderness” (p. 12-13).

“Can we accept the idea that the richest soil has been tainted—or maybe enriched—by the negative?” —William Pope.L

"You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was." —Toni Morrison