These sources explore the complex intersections of technology, biology, and social systems through the lens of information and mathematical modeling. Scientific papers detail how computational frameworks, such as cellular automata and machine learning, can predict chaotic dynamics in everything from camera motion to biological pattern formation. In contrast, cultural essays critique technological colonialism, advocating for "tequiology" and other indigenous practices to reclaim digital autonomy and environmental sustainability. Philosophical reflections link these themes by suggesting that objective reality is woven from information, where human identity and tacit cultural knowledge function as integral, living parts of a distributed system. Ultimately, the collection examines how diversity, complexity, and ethical design are essential for the survival of both biological organisms and modern institutions.

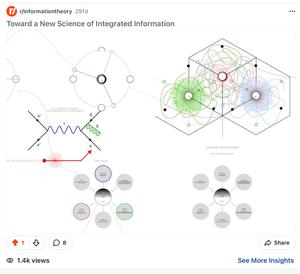

Title: Living Technology : Toward a New Science of Integrated Information

Author 1:

First Name: Branden

Last Name: Collins

Organization: yoo.world

Country: United States

Email: [email protected]

Contact Author: Author 1

Keywords: Topological Quantum Computing, AI, Intelligence, Synthetic Biology, Wearable, Indigenous Wisdom, Information, Consciousness

Abstract: We have created a room-scale many-bodied quantum computer, with each visitor behaving as individual entangled topological Qubits. The turbulent, chaotic nature of social dynamics in our closed environment act as insulators for the encoded information in each Qubit state vector as they enter and exit a series of gates. This, in essence, mirrors the conditions of the quantum vacuum, with fluctuations that result in an emergent spacetime fabric. Our quantum computer is a model of the universe as a single quantum system. The state vectors are therefore encrypted via quantum entanglement as each state...

9 days ago

"I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein's brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops."

- Steven Jay Gould

26 days ago

21 days ago

Many criticisms of the Shannon–Weaver model focus on its simplicity by pointing out that it leaves out vital aspects of communication. In this regard, it has been characterized as "inappropriate for analyzing social processes"[16] and as a "misleading misrepresentation of the nature of human communication".[17] A common objection is based on the fact that it is a linear transmission model: it conceptualizes communication as a one-way process going from a source to a destination. Against this approach, it is argued that communication is usually more interactive with messages and feedback going back and forth between the participants. This approach is implemented by non-linear transmission models, also termed interaction models.[18][3][19] They include Wilbur Schramm's model, Frank Dance's helical-spiral model, a circular model developed by Lee Thayer, and the "sawtooth" model due to Paul Watzlawick, Janet Beavin, and Don Jackson.[9][20] These approaches emphasize the dynamic nature...

I'm very concerned that our society is much more interested in information than wonder.

2.4. Quantum theory is a theory about information

•

The situation and concepts change immediately if quantum theory is understood primarily as a theory of quantum information, only secondarily as a theory of quantum particles and only in a further respect as a theory of quantum fields.

The fact that more and more energy lead to smaller and smaller structures – as implied by quantum theory – sounds implausible for everyday life.

•

On the other hand, it is perfectly evident that more and more information enables an ever more precise localization.

Geosophy is based on the principle that any culture creates the world of its own.

The posthuman conception of thought

I have proposed an energetic theory of mind in which human thought, meaning and memory is understood in terms of the activity of an energy regulating system. Accordingly the human is in essence no different from any other such ‘energistic’ system we may find in the universe. This does not deny that we are extremely complex, nor does it suggest that we will ever fully understand how we function. What should be becoming clearer, though, is the contrast between this conception of human existence and the more traditional humanist one. If we can start to see how the most ‘sacred’ of human attributes, such as conscious experience, creativity, and aesthetic appreciation, operate in ways not dissected from other functions in the universe, then we are moving away from the notion of humans as unique, isolated entities and towards a conception of existence in which the human is totally integrated with the world in all its manifestations, including...

2 months ago