4 days ago

10 days ago

«The computer emerges out of the history of weaving, the process so often said to be the quintessence of women’s work. The loom is the vanguard site of software development. Indeed, it is from the loom, or rather the process of weaving, that this paper takes another cue. Perhaps this paper is an instance of this process of weaving as well, for tales and texts are woven as surely as threads and fabrics. It is a yarn in both senses. It is about weaving women and cybernetics, and is also weaving women and cybernetics together. It concerns the looms of the past, and also the future which looms over the patriarchal present and threatens the end of human history.»

Sadie Plant, «The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics» 1995

10 days ago

Using basket patterns, wampum, songs and stories are ways for the community to remember — they are techniques of decentralizing information, embedding the same story in multiple formats. This was a way of ensuring that the most important knowledge of our communities would be accessible to everyone. Telling by weaving a lesson about technology, medicine, or values in with the story of how a rock formation or a river path was formed helps people remember the story and cements those relationships in people’s minds.

But informatic machines will be found in any situation in which differentiation takes over. Hence weaving, one of the first human activities to be fully industrialized, was also one of the first human activities to be fully computerized.

She wrote of the Analytical Engine: “We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves”

Perhaps Freud's comments on weaving are more powerful than he knows. For him, weaving is already a simulation of something else, an imitation of natural processes. Woman weaves in imitation of the hairs of her pubis criss-crossing the void: she mimics the operations of nature, of her own body. If weaving is woman's only achievement, it is not even her own: for Freud, she discovers nothing, but merely copies; she does not invent, but represents.

'Woman can, it seems, (only) imitate nature. Duplicate what nature offers and produces. In a kind of technical assistance and substitution' (Irigray, 1985: 115). The woman who weaves is already the mimic; always appearing as masquerade, artifice, the one who is faking it, acting her part. She cannot be herself, because she is and has no thing, and for Freud, there is weaving because nothing, the void, cannot be allowed to appear. 'Therefore woman weaves in order to veil herself, mask the faults of Nature, and restore her in her wholeness'...

Where are the women? Weaving, spinning, tangling threads at the fireside. Who are the women? Those who weave. It is weaving by which woman is known; the activity of weaving which defines her. 'What happens to the woman', asks Mead, 'and to the man's relationship with her, when she ceases to fulfil her role, to fit the picture of womanhood and wifehood?' (1963:238). What-happens to the woman? What is woman without the weaving? A computer programmer, perhaps?

Ada's computer was a complex loom: Ada Lovelace, whose lace work took her name into the heart of the military complex, dying in agony, hooked into gambling, swept into the mazes of number and addiction. The point at which weaving, women and cybernetics converge in a movement fatal to history.

It seems that weaving is always already entangled with the question of female identity, and its mechanization an inevitable disruption of the scene in which woman appears as the weaver. Manufactured cloth disrupted the marital and familiar relationships of every traditional society on which it impacted. In China, it was said that if 'the old loom must be discarded, then 100 other things must be discarded with it, fot there ,are somehow no adequate substitutes' (Mead, 1963: 241).

Certainly Freud finds a close association. 'It seems', he writes, 'that women have made few contributions to the discoveries and inventions in the history of civilization; there is, however, one technique which they may have invented- that of plaiting and weaving.' Not content with this observation, Freud is of course characteristically 'tempted to guess the unconscious motive for the achievement. Nature herself', he suggests,

would seem to have given the model which this achievement imitates by causing the growth at maturity of the pubic hair that conceals the genitals. The step that remained to be taken lay in making the threads adhere to one another, while on the body they stick into the skin and are only matted together. (1973: 166-7)

The Jacquard loom was a crucial moment in what de Landa defines as a 'migration of control' from human hands to software systems.

The Analytical Engine was the actualization of the abstract workings of the loom; as such it became the abstract workings of any machine. When Babbage wrote of the Analytical Engine, it was often with reference to the loom: 'The analogy of the Analytical Engine with this well-known process is nearly perfect' (1961: 55).

Ada Lovelace may have been the first encounter between woman and computer, but the association between women and software throws back into the mythical origins of history. For Freud, weaving imitates the concealment of the womb: the Greek hystera; the Latin matrix. Weaving is woman's compensation for the absence of the penis, the void, the woman of whom, as he famously insists, there is 'nothing to be seen'. Woman is veiled, as Ada was in the passage above; she weaves, as Irigaray comments, 'to sustain the disavowal of her sex'. Yet the development of the computer and the cybernetic machine as which it operates might even be described in terms of the introduction of increasing speed, miniaturization and complexity to the process of weaving. These are the tendencies which converge in the global webs of data and the nets of communication by which cyberspace, or the matrix, are understood.

The computer emerges out of the history of weaving, the process so often said to be the quintessence of women's work. The loom is the vanguard site of software development. Indeed, it is from the loom, or rather the process of weaving, that this paper takes another cue.

“The loom is a simple technology, but in the warp and weft of thread lies the weaving of all technologically literate society. Textiles are central to the business of being human, and like software, they are encoded with meaning. As the British cultural theorist Sadie Plant observes, every cloth is a record of its weaving, an interconnected matrix of skills, time, materials, and personnel. “The visible pattern” of any cloth, she writes, “is integral to the process which produced it; the program and the pattern are continuous.” This process, of course, historically concerns women. Around looms, at spinning wheels, in sewing circles, in ancient Egypt and China, and in southeastern Europe five centuries before Christianity, women have woven clothing, shelter, the signifiers of status, even currency.”

Excerpt From: Claire L. Evans. “Broad Band.” iBooks.

Galloway Anti-Computer

Informatic machines prevail in situations of great susceptibility to differentiation. This is why informatic machines rely so heavily on arithmetic discretization. (And why the integers are the most fundamental medium of computation.) But informatic machines will be found in any situation in which differentiation takes over. Hence weaving, one of the first human activities to be fully industrialized, was also one of the first human activities to be fully computerized. I mean computerized in a loose sense. The Jacquard loom of the early 19th Century had software imprinted on articulated cardboard ribbons. The looms used a control mechanism to execute this software on the appropriate hardware (the loom itself). Weaving's own susceptibility to differentiation is what made this process so easy. Threads are spun into discrete strands from a puffy woolen mass. Warp threads are arranged in vertical lines, facilitating discretization in one direction. The weft thread...

We can understand a fragment of textile since it carry’s it’s own data encoded in different layers. Reverse engineering archaeological textiles gives an important testimony to everyday life, farming, trade,migration of nations, religious rituals, art and technical culture. We can deconstruct a textile since it is often constructed chronologically (weaving, knitting, basket weaving) decoding the instructions that were followed by the creator to repeat the process.

The core rope memory was nicknamed “LOL memory”, where LOL stood for the "Little Old Ladies" who assembled it. They were supervised by “rope mothers”, who were often males. But the rope mother’s boss was a woman named Margaret Hamilton.

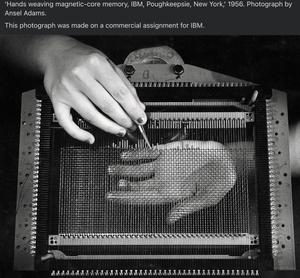

Like all crafts involving weaving, sewing and other forms of textile making that has been historically associated with women, the job of weaving core memory was also entrusted to women. During the first Apollo missions, the software of the Apollo Guidance Computer was physically weaved into a high-density storage called “core rope memory”, which was similar to magnetic core memories. To build the memories, NASA hired skilled women from the local textile industry as well as from the Waltham Watch Company, because of the precision needed to work around the cores with a needle. Sitting across each other at long desks, these women passed wires back and forth through a matrix of eyelet holes, each comprising a magnetic core bead. Passing a wire through the core created a “one,” while bypassing the core created a “zero”.

about 2 years ago

almost 4 years ago